The first chief architect of Tel Aviv – a city destined to become one of the most influential capitals in the world, was a native of Uman, Yehuda Magidovich, the son of Uman women’s hat designer Binyamin Zvi and Uman housewife named Rachel. When one of the founders of the State of Israel and its first prime minister David Ben-Gurion in 1925 organized a ceremonial reception for the most respected guest, Baron Rothschild – he did it in the Great Synagogue of Tel Aviv, built by a man from Uman…

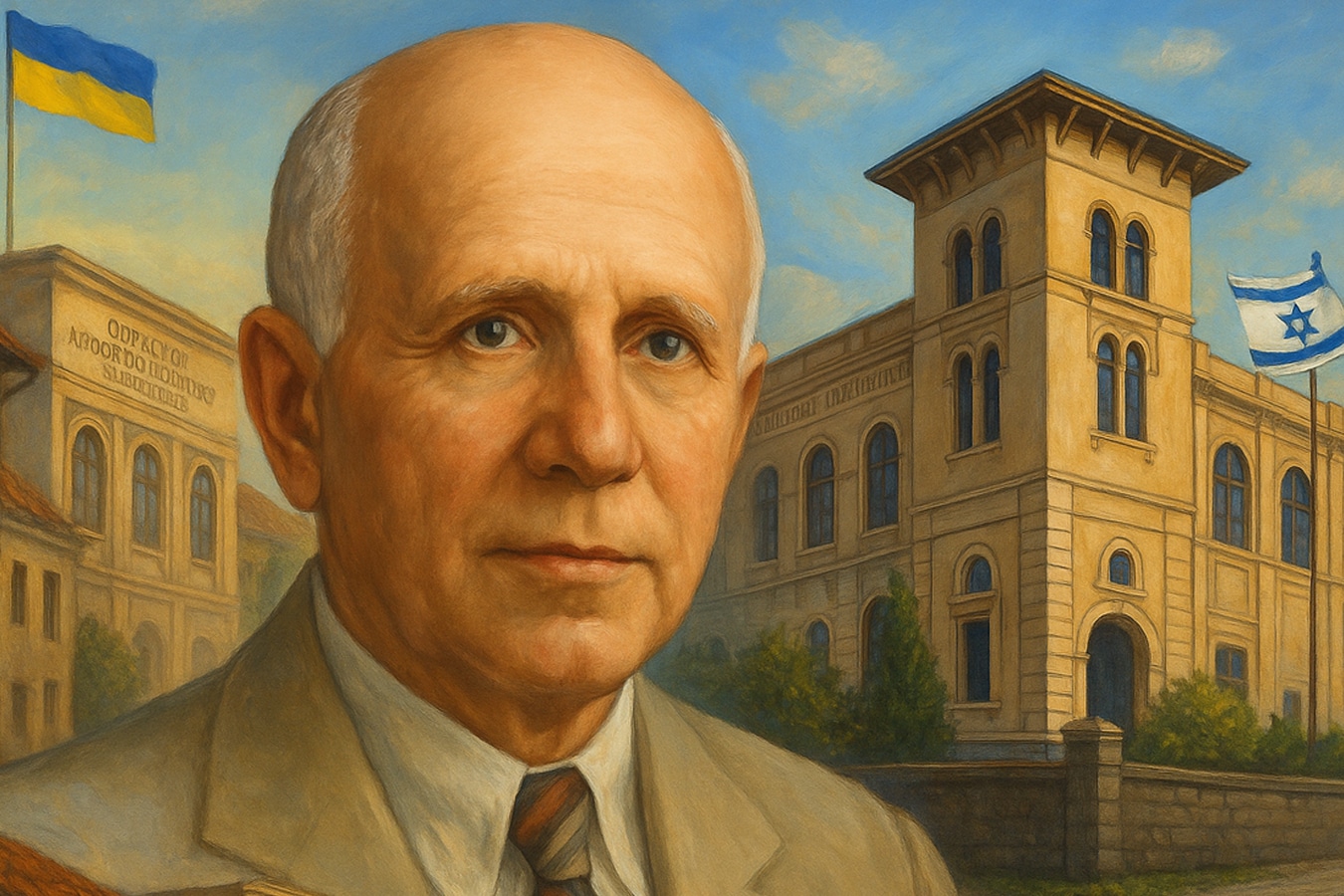

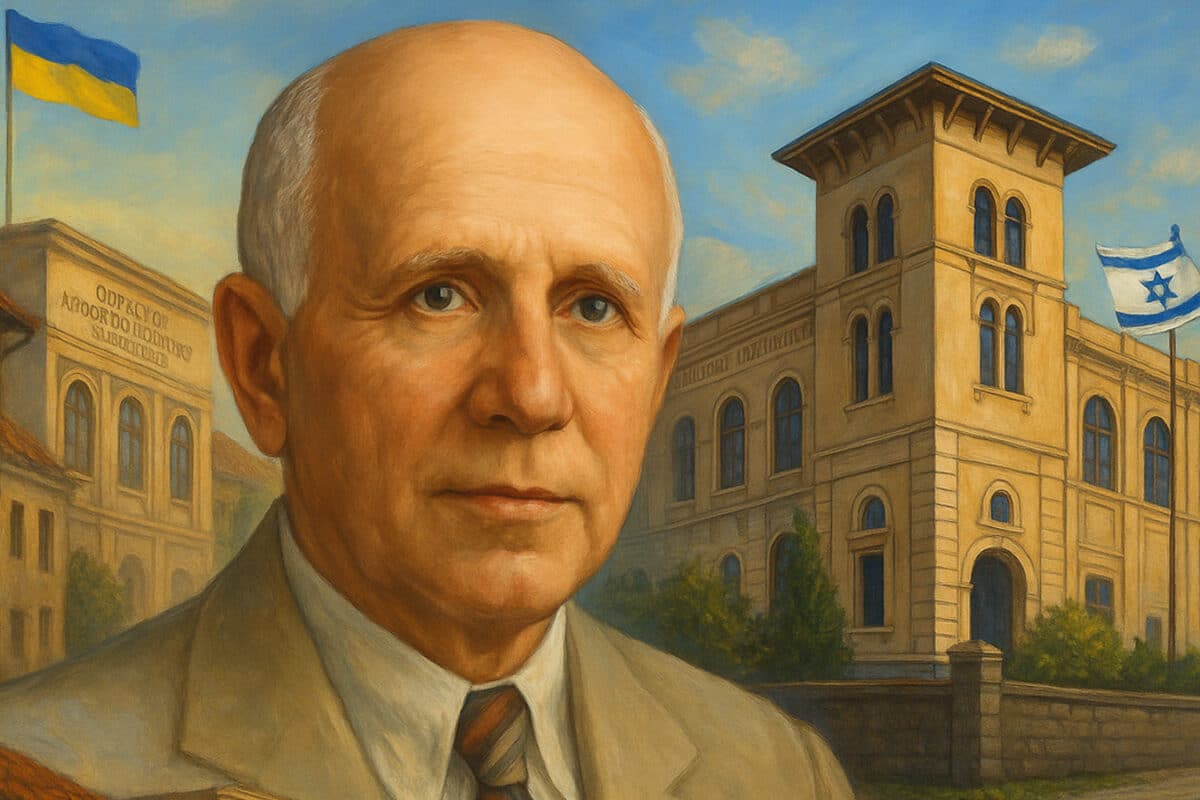

In the section “Jews from Ukraine” – Yehuda Magidovich (January 21, 1886, Uman, Ukraine — January 5, 1961, Tel Aviv, Israel).

From Uman to the White City: The Story of Yehuda Magidovich

In the mid-19th century, the family of hatter Binyamin-Zvi Magidovich lived in Uman. His workshop smelled of steam, pressed felt and fresh ribbons — it was there, in 1886, that a boy named Leib was born, who later all of Tel Aviv knew as Yehuda Magidovich.

His mother, Rachel Sadovaya, was the keeper of the home, and his father was a master who made hats for both officials and young dandies. Studying in a cheder in a small town was the natural beginning for a Jewish boy of that time. But Leib, in addition to prayers and the Pentateuch, was drawn to drawings and unusual shapes. Years later, this passion would lead him in 1903 to Odessa.

Odessa years: brush, pencil and architecture

At the beginning of the 20th century, Odessa was a city where art and commerce mixed in the noisy port. Magidovich studied fine arts in Odessa, then in Kyiv, and then returned to Odessa to study architecture — essentially combining aesthetics with engineering calculation. By 1910 he already had a diploma and his first commissions. Yes, Yehuda Magidovich studied in Odessa, including at an art educational institution.

Most likely (there are no reliable sources of information about exactly where he studied), it was the Odessa Art School with an architectural department, where he received artistic training, and then probably continued his studies at the “Odessa Academy of Arts”, graduating around 1910. This is confirmed by both English- and Hebrew-language sources. In Odessa, he did not just draw facades. Magidovich designed houses that carried echoes of Italian villas and French resort mansions — adapted, of course, to the Odessa climate and local habits. In 1911 he married Atil, née Vogel, and the couple had two sons: Rafael Megiddo and Avshalom Megidovich.

But life in the city was restless. Pogroms, revolutionary rallies and street shootouts forced Jewish communities to self-organize. Magidovich did not stand aside — he took part in Jewish self-defense, and some sources even call him the district commander of one of these units.

1919: Odessa says goodbye

The Civil War was tearing the empire to pieces. In Odessa, families with bundles crowded near the port docks, waiting for permission to leave. Magidovich obtained a forged ID to leave the city, and in the autumn of 1919 he was among the passengers of the steamship “Ruslan”.

With a forged Odessa ID – to the shores of Palestine…

In the autumn of 1919, from Odessa to Palestine, on a journey that made him legendary, the ship “Ruslan” set sail with six hundred Jews on board. Modern Israelis call the “Ruslan” nothing less than “the Mayflower of Zionism, which opened the period of the Third Aliyah”. (The “Mayflower” was the ship that brought the first settlers from England to the shores of the USA). The name “Ruslan” became equally symbolic for Jews — although it was not the first since the beginning of the return of Jews to the Promised Land, its six hundred passengers were the elite of the future state, which was rising from the ashes…

Across the territory of the former Russian Empire, war was raging when in Odessa in all the port houses and even right on the bundles of belongings in the middle of the square, Jewish refugees had gathered. 170 of them were refugees from Safed and Tiberias – subjects of Great Britain, who wanted to return to their native Palestine. The British consul appealed to the Soviet Odessa authorities – and they gave permission to leave. But Odessa would not be Odessa if to those 170 foreigners they did not add another half thousand Jews from Ukraine, Poland and Russia.

They hastily studied the geography of Palestine so as not to “slip up” during the conversation in the Odessa Cheka, and as for the necessary languages — Hebrew and English — each of them already spoke them without extra training. In addition, Odessa professionals made each one a repatriate certificate (“teudat oleh”) with the stamp “Committee of Refugees from Eretz Israel for their return home”.

In the end, “Ruslan” was given the green light — on the journey to distant Palestine, the resident of Uman Yehuda Magidovich went together with future Israeli celebrities — historian Klausner, future editor of the famous newspaper “Haaretz” Glikson, poet Ratosh, doctor of medicine Yassky, artists Konstantinovsky, Frenkel, Navon and Litvinovsky, sculptor Ziffer, future Minister of Education Dinur, future Knesset member Rachel Cohen-Kagan, the mother of future Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin — Rosa Cohen…

This was not just a voyage — Israelis would later call it “the Mayflower of Zionism”. On board were about six hundred people: historians, artists, future politicians, poets. On December 19, 1919, “Ruslan” docked in Jaffa, and Magidovich, along with the others, set foot on the land that would become his new home.

The beginning in Tel Aviv: drawings from Odessa

He did not arrive empty-handed — in his luggage were hundreds of Odessa projects that he had managed to save from the archives. Most of these were plans for villas in the spirit of the Italian and French Riviera, reworked “in the Odessa style.”

Now they were to be transformed into houses on Montefiore Street, Nachlat Binyamin, and in new neighborhoods. Many of these mansions were built in Tel Aviv, reinterpreted already in a Jewish manner. In 1920, he was appointed the first chief architect of Tel Aviv. He was responsible for planning and approving projects, and at the same time designed himself — sometimes in eclecticism with elements of the Moorish style, sometimes in strict Art Deco.

He held this position until 1923, after which he opened his own office.

Friend of the mayor and bold projects

He had known Mayor Meir Dizengoff since the days of Uman. The friendship helped — not in terms of privileges, but in terms of boldness of decisions. Thus, “Galei Aviv Casino” — a building on stilts right above the water — became the city’s calling card. The creative bohemia gathered here, and even Winston Churchill visited. The casino survived the storm of 1936 but was demolished after Dizengoff’s death — during his lifetime the mayor “kept a hand” over his friend’s project. In 1923, Yehuda Magidovich opened his own architectural firm and began to build residential and administrative buildings in the city, which at that time were especially in demand in the young city. To this day, the construction company “Rafael Megido,” named after Magidovich’s son, is well known.

Magidovich worked in the Art Nouveau style — this is what the local version of the modern style is called in Israel. Many interesting buildings were destroyed, for example, the “Kovalkin House” in the Dizengoff Square area, and the casino — “an amazing, spacious, light building, in the spirit of people in high spirits.” But many, fortunately, have survived, including the Great Synagogue on Allenby, the “Levin House,” the “Nordau” hotel, the “Ben Nahum” hotel, and the “Beit Carousel” on Rothschild Boulevard. In the central part of the “Carousel House” there was a fireplace, and inside the windows was suspended a second row of colored stained glass windows.

They hung on rings, and when the air heated by the fire in the fireplace caused them to move slightly, the reflections of the fire played in the glass pieces of the stained glass, and then bright colored spots danced around the room — hence the name of the house. The “House with Columns” on Rambam Street is decorated with columns and arches — elements of the classical style. It was built in 1924 and is now included in the list of houses subject to restoration. The square where this building is located bears the name of Yehuda Magidovich.

The Levin House: terrorist attack and secret mechanism

In 1923, wealthy merchant Yaakov Levin commissioned Magidovich to build a mansion on Rothschild Boulevard. The architect designed a Tuscan villa with a tower whose roof could be retracted, opening a view of the starry sky during the Sukkot holiday. Over the years, the building housed a bank, a British school, the headquarters of the “Hagana,” and later the Soviet embassy. In 1953, fighters from “Etzel” and “Lehi” threw a grenade into the building — a protest against the antisemitic “Doctors’ Plot” in the USSR. People were injured, including the ambassador’s wife. Three days later, the USSR broke off diplomatic relations with Israel — until Stalin’s death.

In 1991, the Levin House, the work of the native of Uman, was declared “an object of special architectural value” and underwent an extremely expensive restoration — with the involvement of the best specialists and equipment specially brought from South Africa. When restorers worked on the tower, they discovered in its highest part a pile of old newspapers and an amazing mechanism, the purpose of which no one knew. They tried to set it in motion — and were shocked when the roof above their heads retracted: the mechanism, invented by the man from Uman, worked perfectly even after 70 years!

After the restoration, the Levin House housed exhibition halls and the office of the famous antique auction house Sotheby’s. In 2006, for 35 million shekels (comparable to the cost of the nearby “Beit Alrov” tower), the villa was purchased by Canadian billionaire Gerry Schwartz. The house, built by a native of Uman, still remains one of the main architectural gems of the capital’s tourist routes.

Architectural style

Over his career he designed more than 500 buildings. The Great Synagogue, villas with columns and domes, houses in Art Deco and in the International Style — all these are works by Magidovich. Even when moving toward modernism, he retained the habit of adding details — arches, small towers, decorative grilles — that referred to his European and Ukrainian experience.

Ukraine in memory and in works

After emigration, he could not return to Ukraine — the Soviet authorities did not allow such contacts. But in his projects one could always find echoes of the “Ukrainian period”: the proportions of the facades, planning techniques, decorative solutions. Israeli guidebooks invariably call him “a native of Uman.” In recent years Ukrainian local historians have also remembered him: publications were issued in the Cherkasy region, and in the Odesa museum in 2024 they even held a review of his Odesa years.

Final and legacy

In 1954, Magidovich suffered a stroke and stopped working. He died in 1961 in Tel Aviv and was buried in the Kiryat Shaul cemetery. He left behind not only buildings, but also an example of how a person from a provincial Ukrainian town can influence the appearance of one of the most famous cities in the world. He was survived by sons and descendants. The family house on Mogiliver Street, which was not included in the list of city heritage sites, was demolished in 2016, and a modern residential building was constructed on its ruins.

In 1993, architect Gilad Dovshni published an extensive book devoted to Magidovich’s work and his contribution to the development of Tel Aviv and Israel’s construction industry. In 2019, a memorial in his honor was installed on the pedestrian Nachalat Binyamin Street.

… The section “Jews from Ukraine” on NAnews — News of Israel tells about people whose roots are in Ukraine and whose contribution is in the history of the Jewish people and Israel. These are stories where Ukrainian experience and Israeli destiny are intertwined in one life path. The biography of Yehuda Magidovich is a vivid example of this connection, from Uman and Odessa to hundreds of buildings in the White City.